The exceptional life and exploits of the greatest hellenic leader gave life to the myth right after his death and over time fueled countless legends.

Alexander was the son of Philip II of Macedon, of the Argead dynasty who claimed descent from Herakles, and of Olympias, daughter of Neptolamos I, king of the Molossians who ruled Epirus and descended from Achilles and therefore from the Nereid Thetis; this child whose life was already marked by divine ancestry was born in July 356 BC in the royal palace of Vergina which was the summer residence of the king of Macedon after the capital was moved to Pella.

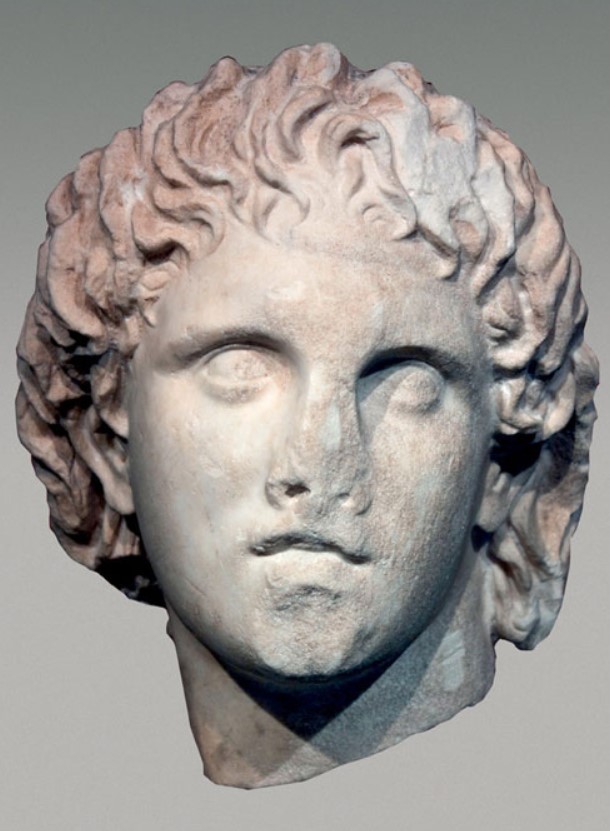

Head of Alexander the Great from Pella, 2nd century BC

The knowledge of the bond with the divinities that came from the blood was for the young Alexander the push continues to stand out. His childhood and then his adolescence passed in the shadow of his mother Olimpiade who always maintained a particular bond with him, while his father took care of his education who entrusted him while still a child to Leonidas of Epirus, probably an uncle of his mother, who organized his days and chose the pedagogues. Among these there was also Callimachus of Acarnania who seems to have no particular teaching skills but was able to establish a strong bond with the boy that would last over time so much so that, when Alexander became king, he accompanied him on the conquest campaigns in Asia. It was Callimachus himself who kept the chronicle of the conquest campaigns, which some ancient commentators already brazenly defined as encomiastic, and from which some of the legends about the life of the young king were born later.

The one who attempted to give Alexander the ability to understand the world and men, which must be a priority in one who must govern peoples and guide nations, was Aristotle, Alexander's tutor from 343 to 341 BC. The lessons that the philosopher of Stagira held in the Nymphaeum of Mieza, near Pella, were not only for the young Alexander but also for a group of scions of the Macedonian aristocracy who were destined to become the lieutenants of the future king, among them also Hephaestion the inseparable friend of Alexander.

Aristotle was the son of Nicomachus, Philip II's doctor who called him to his court to give Alexander lessons in rhetoric and literature, it seems in fact that it was he who introduced him to the Iliad and its heroes and above all Alexander appreciated Achilles who became perhaps his model.

Aristotle gave Alexander a copy of the Iliad that the Macedonian would always carry with him on the battlefields. From the teachings of Aristotle which also ranged in botonics and zoology, Alexander developed an interest in plants and animals and military enterprises in distant lands were also an opportunity to collect rare or unknown plants and exotic animals with which he made build a sort of zoo in his palace.

One of the first legends about Alexander is linked to the teenage years, the one that tells how the strong bond that united him to his horse Bucephalus was born and of which the best known version is the one that Plutarch reports in the Parallel Lives.

It was an adolescent Alexander who followed Philip with part of his cohort to the horse pens to try out a beautiful black horse that Philonicus the Thessalian wanted to sell him for thirteen talents. The price was very high and moreover it was immediately seen that the horse was capricious and that it would have been difficult to tame and ride him; Philip's grooms and some known as skilled horsemen tried but failed to mount him. Philip resolved that the horse was still wild and to take it away but meanwhile next to him Alexander was muttering that the horse was beautiful and it was the men who didn't know how to handle it. Philip heard the words of his son thought to put him to the test since he criticized those who were older had to know more than him.

Alexander tames Bucephalus. Painting by L. Angelini from the 19th century model of the bas-relief above the door for the Royal Palace of Caserta- Caserta IT

"You rebuke," said he, "those who are older than you, as if you knew more than they and could use that horse more than they can." And Alexander: "I certainly would," he replied, "use it better than anyone else." "And if you don't use it then," added Philip, "what penalty will you pay for this temerity of yours?" - "I, by Jupiter," follow Alexander, "I will pay the price for the horse."

Having made a bet with his father, Alexander went to the horse, took the reins and with them placed it in front of the sun; in fact, the young man had observed that the horse froze when it saw his shadow. He then began to caress it, pat it and pat it, moving around it so that the animal gradually stopped snorting and although he was still visibly restless, Alexander took off his cloak and with a leap he was able to mount on the back, firmly holding the reins. But the horse was stamping and so he loosened his grip on the bridle, tapped his foot on the side and the horse galloped off.

After making him run, he returned to where his father Filippo was, worried but at the same time proud of his son who, when he got off the horse, kissed on the head and to whom he said: Son, look for a kingdom that suits you: Macedonia is too small for you.

From that day on, that horse which was given the name of Bucephalus was ridden only by Alexander.

Arrian, historian of the first century BC, in his writing Anabasis of Alexander explains reason why the horse was given the name of Bucephalus:The head of an ox was stamped on it as a mark, which is why they say it bore that name; others instead argue that, being black, he had a white mark on his head, resembling the head of an ox.

The mark resembling the head of an ox indicates an almost certain Thessalian origin of Bucephalus, in fact the Thessalians who had been horse breeders for centuries had the custom of marking the animals intended for foreign market.with the archaic letter alpha, very similar to the stylized head of an ox.

Alexander rode Bucephalus for many years and in many of the battles he faced; the bond between them was very strong and Alexander, after the horse's death from wounds sustained in a fight, wanted to give his name to one of the cities he founded on his way to the conquest of India.

Alexander and Hephaestion during a deer hunt, 4th century BC – Museum of Pella EL

Alexander's first time on the battlefield was at Chaeronea on August 12, 338 BC when the Macedonian army clashed with that of the league of Greek cities who resented the influence of the barbarians, as they considered the Macedonians, and their arrogance in having proclaimed themselves regents of the temple of Delphi, the one dedicated to Zeus. In that battle the army was led by Philip II and his father wanted to entrust Alexander with the command of one of the cavalry wings and although young he demonstrated all his skills and qualities as a fighter. In that battle the Macedonian army adopted for the first time the sarissa, the long spear that Philip had wanted to give his infantry an advantage not only in clashes with the hoplites but above all with the cavalry because they prevented the advance of the horses. The Macedonian strategy was based on the combined action of heavy infantry and cavalry, the technique which would later allow Alexander to excel on the battlefields.

Alexander at the Battle of Chaeronea, right, fighting a Theban. Relief from a funerary stele

First part: rev.0 by M.L. ©ALL RIGHTS RESERVED (Ed 1.0 - 22/03/2023)